A Plug for Classism in Science

One of the appeals of science, I think, is that it has the appearance of egalitarianism. If your ideas and methods are good, then your work will be meaningful and respected by others inside and outside of the scientific community. In principle, it doesn’t matter where you do the work, because we’re all interested in the truth, and if the truths you find and communicate are more valuable than the truths I find and communicate, then you’ll reap proportionally more rewards.

It doesn’t take much thinking to realize that this is absurd - the name brand of your advisor or of the institution at which you work or received your degree carries a lot of weight. So too does the socioeconomic status that you come from - if you come from a lot of money, then you can probably afford to spend your summers volunteering in research labs. If you don’t come from a family with resources to support you, or if your family actually relies on you to help support them, then you’re not volunteering in any lab. Instead, you’re doing whatever you can to make sure everyone is fed, housed, and clothed. I’ve never once seen a line on a scientific CV where someone lists the amount of work they put in in order to provide for themselves or their loved ones.

All this is admittedly distasteful. Especially, I think, in the US, where we want to believe that you get what exactly what you work for. So maybe it’s a little suprising that I think there are some places in science where we should respect class differences and what they mean for our work.

When does your class matter for your research?

In short, when you need a lot of resources. When do we need a lot of resources? Frequently. More often, in fact, than we admit.

The problem with power

Earlier this summer, I was fortunate enough to attend the BITSS summer workshop on transparency. The experience was a good one, and it was interesting to be among researchers interested in maintaining integrity in science, especially since we all came from a diverse set of fields. Everyone was there for the same underlying motivations, but each of us had encountered problems that were more unique to our respective fields.

One of the problems that plagues psychology these days is that it’s totally acceptable to run dramatically underpowererd studies. In order to detect an effect, we need to run a study with the appropriate level of power. If we don’t have the appropriate level of power, we might fail to detect an effect that exists. This also means that if we run an underpowered study, we run a good risk of finding the opposite effect (i.e. an intervention hurts grades when it actually helps) or dramatically overstating the size of the effect (e.g. the intervention boosts grades by 2 grade points, when it actually only boosts grades by .25 grade points). These are clearly problems.

The usual advice is to determine in advance how many participants you need in order to detect the effect with a power of .8 (i.e. detect the effect 80 % of the time you run a study). In order to determine sample size, you need to know what the effect size (often measured as Cohen’s d) is and what your levels of alpha and power are (typically .05 and .80, respectively).

The part where psychologists get stumped is in estimating the effect size. There’s a lot of reasons we get stumped, and also a lot of reasons why knowing that number to the precision we need is nearly impossible. In a talk given at the workshop, Leif Nelson suggested that we can’t rely on the usual sources of information for d because they are each frought with problems.

- We can’t use pilot studies, because estimating the effect size from a pilot with a small group of people will itself give wildly variable estimates.

- We can’t use published literature because of the strong effects of publication bias which lead to the effect size reported in the literature being overstated (i.e. only large effects get published)

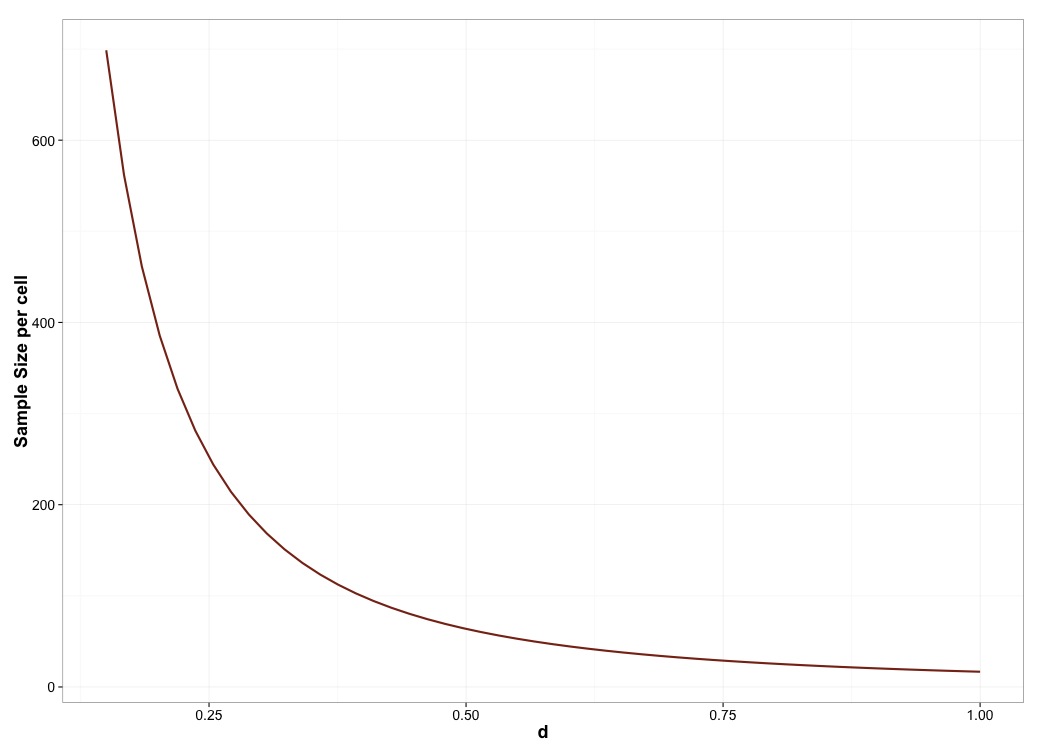

- And we can’t use our intuition because small changes in effect size call for large changes in sample size. Here’s a plot of effect size (cohen’s d and the sample size required to detect an effect 80% of the time with an alpha level of .05) for an independent samples t-test:

Because this is nonlinear, small changes at the right part of the curve can lead to big differences in the number of people required. For instance, the difference between an effect size of .25 and one of .3 is about 75 people per group.

Anyway, all this is just to illustrate that the usual method of deciding upon the number of people isn’t really working. So what’s an investigator to do?

Leif’s suggestion is to decide how important the problem is to you, then pick the amount of time and money you’re willing to throw at it and run participants until you reach one of these thresholds. Once that threshold is reached, if your data don’t let you reject the null, then that effect is too small for you to study.

That’s it. No science of _____ for you. You don’t have the money or the resources.

Now, initially this rubbed me the wrong way. This inevitably means that the people with lots of money and/or resources get to play with more research problems than those who don’t, and this seems absolutely unfair.

But it’s hard to see an alternative. Life is often unfair, and if we want to study people, I think we have to accept that some things will require more resources than others. If you don’t have the resources, then you just can’t study it. It doesn’t matter whether you’re trying to study self-reported emotional experiences or neural responses to emotionall stimuli. If you don’t have the participants for either or a scanner for the latter, no amount of moral outrage over the injustice will change that basic fact.

Is it hopeless? Perhaps not…

A potential solution

Now, one researcher may not be able to reach the required sample size to study some effect. However, if many of them band together to study some phenomenon everyone agrees is important, and if they can all consent to using the same methodology, there’s no reason why the experiment can’t be run en masse across multiple locations. Think of it as kind of like the sometimes-used adversarial collaborations, but done en masse. This obviously opens up its own set of problems (introducing more variability due to slight variations between labs), but it seems like a promising alternative to the idea that researchers operating under certain circumstances just can’t study some subset of effects that, may be small but important or interesting.